A good place to start to understand the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) response to the present crisis, its unprecedented lending, is by really understanding its response to the last one, which had been unprecedented until now. Before we are able to fully analyze the Fed’s response to the present crisis, which is still evolving and ongoing, the press or public will likely need to pursue Freedom of Information Act lawsuits for release of detailed information, as Bloomberg had to do the last time. Regarding the last crisis, the most extensive analysis of the Fed’s various lending programs was done by Felkerson (2011). Therefore, this series of posts will start there, by summarizing and explaining his analysis.

As many market participants and others know, the Fed manages the federal funds rate. This is the “standard tool” (targeting the rate, not the money supply) that the Fed uses to manage the economy. The fed funds market is an uncollateralized market in which depository institutions and government sponsored enterprises lend to each other overnight. The Fed participates in this market via its primary dealers until the effective fed funds rate falls in line with the Fed’s target rate.

Also, the Fed directly sets the discount window rates and terms (duration, haircut (overcollateralization), and collateral), which is available to commercial banks and other depository institutions. These are the key rates, and they went from approximately 5+% to 0% from August 2007 to December 2008. (It is important to keep in mind that the duration and other lending terms are key features of these arrangements.)

After hitting the zero-lower bound (in terms of short-term interest rates), the Fed engaged in quantitative easing, as explained here. Regarding the Fed’s balance sheet, the assets are publicly available here, and the corresponding increases are captured on the liabilities side as reserves (or excess reserves, with interest on excess reserves (IOER) starting in October 2008).

Fed Lending Starts – General

In addition to the reduction in these short-term interest rates (as well as IOER and elaborate forward guidance), the Fed created several special facilities. As Felkerson says, “The authorization of many of these unconventional measures would require the use of what was, until the recent crisis, an ostensibly archaic section of the Federal Reserve Act—Section 13(3), which gave the Fed the authority ‘under unusual and exigent circumstances’ to extend credit to individuals, partnerships, and corporations.” This point will become even more salient when we shift to the present period.

One of the distinguishing aspects of Felkerson’s methodology is the following: “To provide an account of the magnitude of the Fed’s bailout, we argue that each unconventional transaction by the Fed represents an instance in which private markets were incapable or unwilling to conduct normal intermediation and liquidity provisioning activities…. Thus, to report the magnitude of the bailout, we have calculated cumulative totals by summing each transaction conducted by the Fed.”

“Each transaction” are the critical words. When each transaction is counted, the total lending would be considerably higher than a methodology that counts each contract, for example, repo contract since they are often rolled over, only once, depending on how each transaction is defined.

Now, the alphabet soup of lending facilities as ordered and explained by Felkerson:

- Term Auction Facility (TAF) – rate determined by auction, 28-day or 84-day term. Lending to depository institutions so that they could avoid the stigma associated with using the discount window, also acceptance of a wider range of collateral. Felkerson summarizes, “The TAF ran from December 20, 2007 to March 11, 2010…. A total of 416 unique [foreign and domestic] banks borrowed from this facility…. The Fed loaned $3,818 billion in total over the run of this program.”

- Central Bank Liquidity Swap Lines (CBLS) – “The facility ran from December 2007 to February 2010 and issued a total of 569 loans…. In total, the Fed lent $10,057.4 billion to foreign central banks over the course of this program as of September 28, 2011.” His percentages calculated for each central bank were: ECB 80%, BoE 9%, SNB 4%, BoJ 4%, All Others 3%.

- Series of term repurchase transactions (ST OMO) – “28-day repo contracts in which primary dealers posted collateral eligible under conventional open market operations…. In 375 transactions, the Fed lent a total of $855 billion dollars.”

- Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) – 18 primary dealers participated. Lending totaled “$1,940 billion.”

- TSLF Options Program (TOP) – 11 primary dealers participated. Lending totaled “$62.3 billion.”

Fed Lending Continued – Bear Stearns Specific

Two of Bear Stearns’ hedge funds had considerable exposure to subprime mortgages, and this led to the whole firm experiencing liquidity problems. Specifically, regardless of the quality of its collateral or the relative concentration of the troubled assets to one part of its business, the firm was shut out of the tri-party repo market, on which it depended for liquidity to operate its business.

As Felkerson writes, in response, “on March 13…[it informed the Fed] that it would most likely have to file for bankruptcy the following day should it not receive an emergency loan. In an attempt to find an alternative to the outright failure of Bear, negotiations began between representatives from the Fed, Bear Stearns, and J.P. Morgan. The outcome of these negotiations was announced on March 14, 2008 when the Fed Board of Governors voted to authorize the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) to provide a $12.9 billion loan to Bear Stearns through J.P. Morgan Chase against collateral consisting of $13.8 billion.”

To facilitate the actual sale to Bear Stearns, the Fed created a special purpose vehicle (SPV) called Maiden Lane I. As Felkerson explains, “Maiden Lane, LLC would repay its creditors, first the Fed [$28.82 billion] and then J.P. Morgan [$1.15 billion], the principal owed plus interest over ten years at the primary credit rate [one of the discount window rates] beginning in September 2010. The structure of the bridge loan and ML I represent one-time extensions of credit. As onetime extensions of credit, the peak outstanding occurred at issuance of the loans.”

On March 16, 2008, the same day that JPMorgan Chase issued its provisional merger with Bear Stearns, the Fed set up the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF). This facility was meant to prevent these investment banks (banks that were not eligible to go to the discount window for assistance) from experiencing liquidity issues, which could quickly become solvency issues.

I use the word “prevent,” because theoretically, that is the idea with any backstop, including FDIC deposit insurance. Its creation is meant to instill confidence, and banks only avail themselves of the facility when its mere existence is not enough to prevent a run. (All of these liquidity issues can be characterized as runs.) However, just as with the discount window, the use of these facilities can come with stigma, with investors and market participants questioning the general viability of the firm when it resorts to using the lending facility.

Felkerson summarizes the PDCF as follows: “Initial collateral accepted in transactions under the PDCF were investment grade securities. Following the events in September of that year, eligible collateral was extended to include all forms of securities normally used in private sector repo transactions…. The PDCF issued 1,376 loans totaling $8,950.99 billion…. [T]he five largest borrowers account for 85 percent ($7,610 billion) of the total. Eight foreign primary dealers would participate in the PDCF, borrowing just six percent of the total. The PDCF was closed on February 1, 2010.”

Fed Lending Continued – AIG Specific

In the wake of Lehman Brother’s bankruptcy filing on September 15, 2008, to prevent AIG from failing, the Fed first created a revolving credit facility (RCF), “on September 16, 2008, which carried an $85 billion credit line; the RCF lent $140.316 billion to AIG in total,” and the Fed created a secure borrowing facility (SBF) to facilitate repo transactions; “[c]umulatively, the SBF lent $802.316 billion in direct credit in the form of repos against AIG collateral” (Felkerson).

Then Maiden Lane II “was created with a $19.5 billion loan from the FRBNY to purchase residential MBS from AIG’s securities lending portfolio,” and these proceeds were used to pay off SBF (Felkerson).

The Fed later created Maiden Lane III to “address the greatest threat to AIG’s restructuring—losses associated with the sizeable book of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) on which it had written credit default swaps (CDS)…, [which] was funded by a FRBNY loan to purchase AIG’s CDO portfolio, [totaling] $24.3 billion” in lending (Felkerson).

Then, “on December 1, 2009…FRBNY received preferred interests in two SPVs created to hold the outstanding common stock of AIG’s largest foreign insurance subsidiaries [AIA/ALICO transactions]… On September 30, 2010 an agreement was reached between the AIG, the Fed, the U.S. Treasury, and the SPV trustees…. [They] announced the closing of the recapitalization plan…, and all monies owed to the RCF were repaid in full January 2011” (Felkerson).

Let us pause at this point and consider that the United States central bank, whose dual mandate is price stability and full employment, and which is really not supposed to be buying anything but government-issued or, at best, government-backed (Agency MBS) securities, was purchasing CDOs of uncertain value, considerable opacity and high risk to help one corporation, AIG, which had become greedy and irresponsible. The total lending ($140 + $802 + $20 + $24 + $25) was over $1 trillion dollars. It is worth repeating. AIG got over $1 trillion in aid from the Fed while regular Americans often lost their homes, lost their jobs, went bankrupt or were plunged into poverty.

Fed Lending – The Alphabet Soup Continued

However, this was not the end of the Fed’s lending to help private industry, literally entire industries. Within the money market mutual fund (MMF) industry, the Reserve Primary Fund broke the buck on September 16, 2008. It not only held Lehman’s commercial paper but had actually increased its exposure to the firm prior to its bankruptcy.

This event triggered a run on the entire industry, which was over $2 trillion at the time. (Institution investors generally treat money market funds like depository institutions, that is, they seek capital preservation not returns.) The redemptions triggered a downward spiral in asset prices as the funds were forced to sell assets to meet them.

AMLF

The Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) was created on September 19, 2008 to facilitate nonrecourse loans to MMFs at the primary credit rate. “Two institutions, J.P. Morgan Chase and State Street Bank and Trust Company, constituted 92 percent of AMLF intermediary borrowing…. Over the course of the program, the Fed would lend a total of $217.435 billion…. The AMLF was closed on February 1, 2010” (Felkerson).

CPFF

The mutual fund industry’s distress resulted in a flight to safety, which had an adverse effect on the commercial paper market. With companies issuing commercial paper unable to find enough buyers, the commercial paper market froze. “To address this disruption, the Fed announced the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) on October 7, 2008. [The SPV purchased] highly rated ABCP and unsecured U.S. dollar-denominated CP of three-month maturity from eligible issuers…. The cumulative total lent under the CPFF was $737.07 billion…. The CPFF was suspended on February 1, 2010” (Felkerson).

Note that even “highly rated ABCP” are still opaque instruments, and conservative institutional investors assess the risk of the instrument typically by the issuing bank not the underlying collateral.

TALF

These liquidity provisions were still unable to stabilize financial markets, which had transitioned to an originate-and-distribute model, and “the Fed announced the creation of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) on November 25, 2008. Operating similarly to the AMLF, the Fed provided nonrecourse loans to eligible borrowers posting eligible collateral, but for terms of five years. Borrowers then would act as an intermediary, using the TALF loans to purchase ABS [Asset Backed Securities]…. Although the Fed terminated lending under the TALF on June 30, 2010, loans remain outstanding under the program until March 30, 2015. The Fed loaned in total $71.09 billion” (Felkerson).

Summary of Fed Lending in 2008

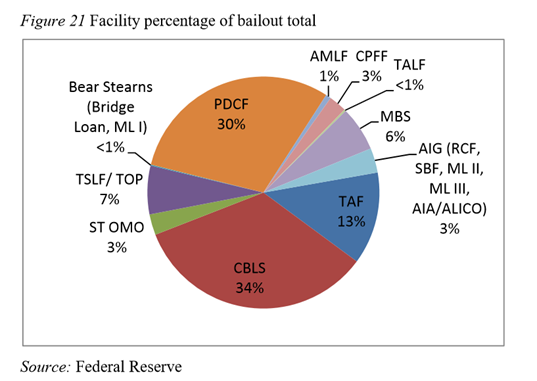

Felkerson summarizes all the Fed’s lending programs as follows and provides the figure below: “When all individual transactions are summed across all unconventional LOLR [lender of last resort] facilities, the Fed spent a total of $29,616.4 billion dollars! Note this includes direct lending plus asset purchases…. Three facilities—CBLS, PDCF, and TAF—would overshadow all other unconventional LOLR programs, and make up 71.1 percent ($22,826.8 billion) of all assistance.”

Note that MBS data can be found on the SOMA site. (Felkerson separated them from the traditional Treasury securities that are a standard part of open market operations.) Felkerson notes that “[i]f the CBLS [central bank liquidity swaps] are excluded, 83.9 percent ($16.41 trillion) of all assistance would be provided to only 14 [of the largest financial] institutions [in the world]…. [And] the six largest foreign-based institutions would receive 36 percent ($10.66 trillion) of the total bailout.”

As calculated by Felkerson, the Fed’s lending programs in response to the 2008 financial crisis was massive, double the nominal GDP at the time; the institutions directly benefiting were relatively few, and the risks were high. The legal justification for what was at the time unprecedented actions was flimsy, the Federal Reserve Act—Section 13(3), if not illegal.

What was the reward for the American people, whose lives and tax dollars were ultimately at stake, for all of this Federal Reserve support for a financial system that had grown too large, too corrupt and too greedy? What did you get from the Fed’s astronomical amounts of lending? You got a system that learned how to exploit the existing order and you, the American people. The Federal Reserve has become captive to these financial players and markets, and you, the American people, are its victims.